Dig Houses of the West Bank

About Dig Houses of the West Bank

About

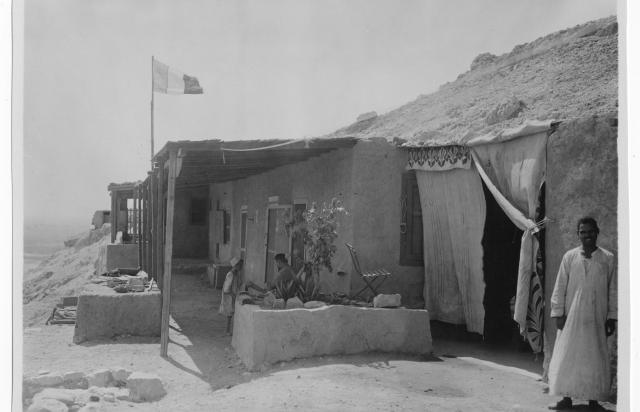

The West Bank of Luxor is largely notable for its ancient monuments and striking geological formations. The desert landscape is marked by several necropoleis, such as the Valley of the Kings, the Valley of the Queens and Western Wadis, the tombs of the nobles, temples and chapels, and settlements that date to various periods of Egypt’s ancient past. It is here that many archaeologists of early Egyptology worked and made world-changing discoveries. Annually spending several months at a time supervising excavations meant that living “on site” became a necessity. At the turn of the twentieth century, foreign archaeologists began constructing “dig houses,” that is, houses in which archaeologists lived and studied, at or near excavation sites throughout Egypt. In Luxor, other houses, like Wilkinson House and Bayt Madinah, were repurposed ancient Egyptian tombs. Over time, several dig houses were built, modified, and occasionally torn down on the West Bank of Luxor, and some houses are still used today as dig houses or as museums, like Carter House.

The Dig Houses of the West Bank explores several historic dig houses: Carter House, Metropolitan House, German House, Old Chicago House, Waseda House, Stoppelaere House, Mond and Davies House, Wilkinson House, Theodore Davis House, and Bayt Madinah. Their rich histories include not only the excavation lives of the pioneers of Egyptology, but also visits from elite international guests. Most of the dig houses are built within the archaeological landscape of Luxor, amid tombs and temples, integrating ancient and modern as reminders that the modern history of Egypt and Egyptology is deeply embedded in the history of ancient Egypt.

Each Dig House page contains a history of activity in the houses including construction, teams that used the houses as headquarters during excavation, and expansion projects. In some cases, like at Bayt Madinah, or the French House, there are records of frivolity that bring charming life to the history of archaeology. Egyptologists did not just work at these sites; they also had fun!

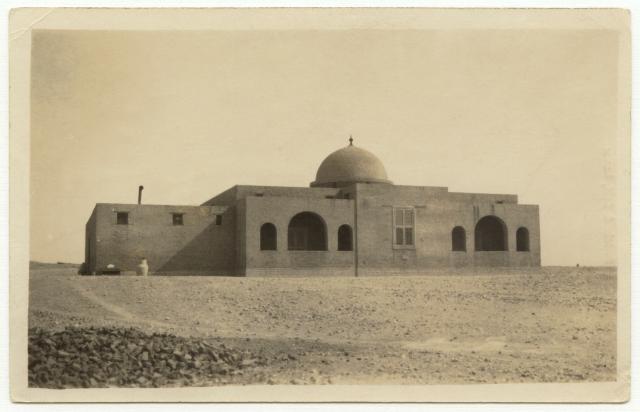

Moreover, the dig houses serve as monuments of Egypt’s modern architectural achievements. Many of the dig houses incorporate features of Coptic and Islamic architecture, as well as revitalize the use of mud brick that was popularized by architects Hassan Fathy and Somers Clarke. Domes characterize several of the dig houses, which are prevalent in both Coptic and Islamic architecture, and some houses include exquisite mashrabiya, an intricate latticework found in Islamic architecture.

Created by: Briana C. Jackson (Digital Humanities Postdoctoral Fellow 2023-2025)

With contributions by: Dr. Kent Weeks

A large set of the archival material used for the building of this database was shared with the Theban Mapping Project by Marcel Maessen and Monica Maessen of the T3.wy Foundation, to whom the TMP is most grateful. Special thanks are also given to the following institutions for their generous collaboration: Griffith Institute, the Egyptian Museum in Turin, Tarek Waly Center, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Waseda University, the Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures - University of Chicago (ISAC), the Schweizerisches Institut (Swiss Archaeological Institute), the Deutsches Archäologisches Institut (DAI), and the Peggy Joy Egyptology Library.

Site History

In Luxor, the earliest on-site dig houses were Schiaparelli House (1901), built into the cliffs overlooking Dayr al Madinah, Mond and Davies House (1902), overlooking Dayr al Bahri, and the German House (1905), situated near the Ramesseum, or the Temple of Rameses II. Unfortunately, there are some lacunae in the timelines for some of the houses where unknown activity took place, or where the houses were abandoned for some time, as in the case of the Stoppelaere House. Some houses were completely demolished and either rebuilt on the site of the original, such as the three phases of the German House, or abandoned entirely, as in the case of Old Chicago House, which was reestablished on the East Bank. Waseda House is the most recent dig house on the West Bank, having been built in 1976.

Many of the houses are still used as dig houses, such as Metropolitan House, German House, and Bayt Madinah, but others have been converted for other purposes, such as Carter House, which is now a museum, and Stoppelaere House, which is now a digital and archiving training center.

Dating

This site was used during the following period(s):

Conservation

Conservation History

Many of the existing houses were renovated, expanded, or rebuilt numerous times since their first construction. Carter House and Stoppelaere House were not simply renovated but became major conservation projects that were funded by USAID and the Tarek Waly Center respectively. In the late 1970s, Davis House also underwent significant restoration, carried out by John Romer. More information on these projects is found on their individual pages.

A lot of renovations included modernizing the houses by outfitting them with electricity and plumbing, since these features were not available in the earliest history of some of the houses' construction. But also, major expansions, namely additional bedrooms and laboratories, were necessary due to the ever increasing number of team members working in the archaeological missions.

Bibliography

Romer, John. Valley of the Kings. London: Rainbird, 1981, repr., 1988; New York: Morrow, 1981. Transl. in French as: Histoire de la vallée des rois. Paris, 1991.

Salmas, Anne-Claire 2023. The café of Deir el-Medina: another archaeological prank. In: Almansa-Villatoro, M. Victoria, Silvia Štubňová Nigrelli, and Mark Lehner (eds), In the house of Heqanakht: text and context in ancient Egypt; studies in honor of James P. Allen. Leiden: Brill, 2023. Pp. 341-355.

Salmas, Anne-Claire. Morceaux de bravoure et traits d’humour: à propos de deux peintures de Bernard Bruyère dans la maison de fouilles de Deir el-Medina. Bulletin de l'Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale 118 (2018): 403-440.

Serageldin, Ismail. Hassan Fathy. Alexandria: The Bibliotheca Alexandria, 2007.

Steele, James. An Architecture for People: The Complete Works of Hassan Fathy. Eastbourne: Gardners Books, 1997.

Strudwick, Nigel. Nina M. Davies: a biographical sketch. Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 90 (2004): 193-210.

Teeter, Emily. Chicago on the Nile: a century of work by the Epigraphic Survey of the University of Chicago. ISAC Museum Publications 2. Chicago: Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures, 2024: 273-307.

Warner, Nicholas. Clarke/Fathy: Reviving Traditions. In: El-Wakil, Leila (ed.). Hassan Fathy: An Architectural Life. Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press, 2018: 262-269.