Stoppelaere House

About

About

Situated on the high hilltop at the entrance to the Valley of the Kings, the Stoppelaere House overlooks both Carter House and Waseda House. It was designed by renowned Egyptian architect Hassan Fathy in 1950 and commissioned by conservator Alexandre Stoppelaere. The house is characterized by what Hasan Fathy called the “vernacular style” which he famously perfected during the construction of New Gourna. This style incorporated traditional Nubian and Islamic architectural styles, with mud brick as the primary construction material. Although Stoppelaere House may be considered architecturally similar to the other historic dig houses that draw largely on Coptic architecture, Fathy’s design might be interpreted more as a preservation of local traditional architecture, especially as it was designed after the houses Fathy constructed at New Gourna. The Stoppelaere House is one of the few surviving buildings of Fathy’s architectural legacy.

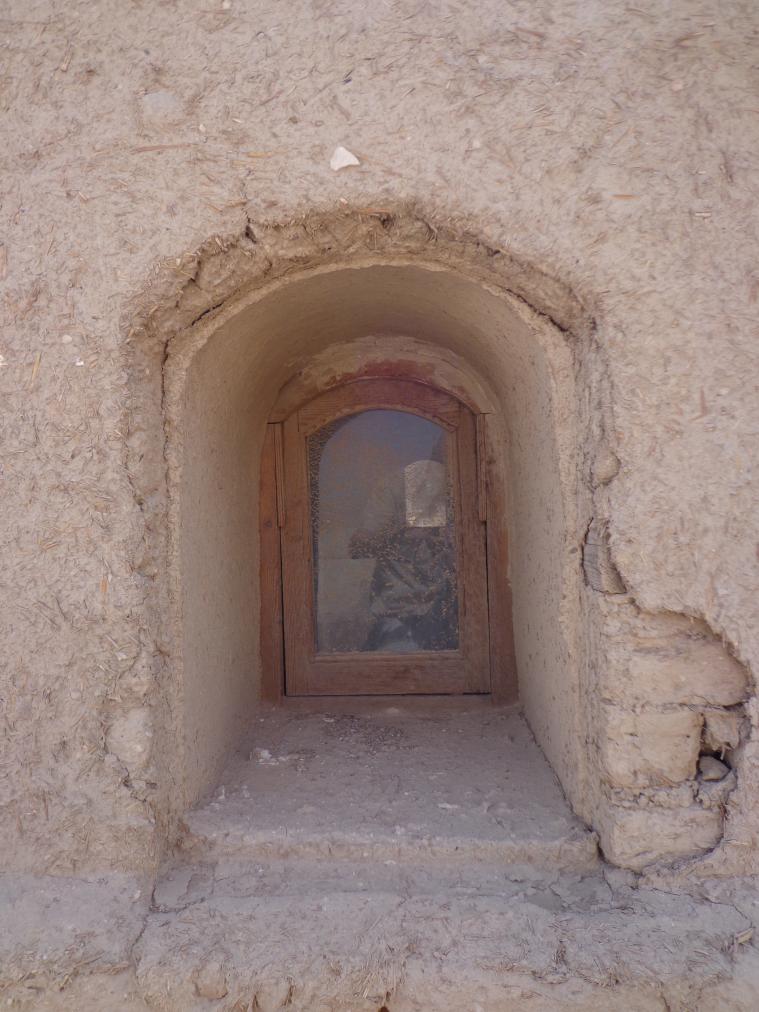

The Stoppelaere House is a complex composed of a sprawling house surrounded by three courtyards and a portico or garden on the south side of the house. Hassan Fathy designed it to function as both a private house as well as use for archaeological study. Bedrooms are situated on both extremes of the house, with the common areas, office, and drafting room arranged in the middle. A large dome, punctuated by small arched windows covers the common room, while two smaller domes, also punctuated by small arched windows, each cover a bedroom in the north east corner of the house. The domes are comprised of stepped squinches, giving the base of the domes their signature square shape. A flatter dome covers the courtyard in the south west portion of the house. Interior rooms have barrel vaulted ceilings, and several doorways are also barrel vaulted.

The entire house is made of mud brick with minimal use of wood, which was reserved for the roofing. Load bearing walls had foundations of limestone blocks. The mud brick was then plastered over. Later additions of electric wiring caused some damage to the fragile mud brick, and the wood was prone to termites. Conservation efforts have significantly restored the house, including adding new windows and doors decorated with mashrabiya, or latticework, common in Islamic architecture.

Fathy’s sketches do not match the final layout, but the Theban Mapping Project was able to provide an as-built plan following their 2000 survey. This plan, compared with Fathy’s plans, shows that modifications were made at several points throughout the house’s vague history.

Now the house is outfitted with an electronics workshop, server room, multi-purpose room for lectures and seminars, offices, archive room, and a studio in the basement for photography and data processing.

Site History

Between 1946 and 1947, Alexandre Stoppelaere was assigned by the Antiquities Service to renovate several Theban tombs such as those of Rekhmire, Menna, Kheruef, and Nefertari. In 1950, Stoppelaere commissioned architect Hassan Fathy to construct what is now the Stoppelaere House, which he used until either 1952 or 1957 (reports on the year Stoppelaere departed the Theban tombs projects vary).

The house fell out of use and was abandoned after 1977 until the Theban Mapping Project conducted a thorough survey of the house in 2000. The T3.wy Foundation, headed by Marcel and Monica Maessen, carried out documentation research at the house in 2010. In 2016-2017, the Tarek Waly Center undertook a major conservation project to restore the house and transform it into a digital recording and archiving training center.

Dating

This site was used during the following period(s):

Exploration

Conservation

Conservation History

Because the house had fallen into extreme disrepair after having been abandoned in 1977, the conservation efforts undertaken by the Tarek Waly Center were rigorous. Largely, the damage was focused on the termite-ridden wood and the mud brick of the domes and vaults that had severe cracks from earlier electric wiring that was added some time after the house’s original construction. Other damages include a poor sewage system and plumbing that caused water damage in the walls, leaving several cracks in the mud brick and plaster. The foundation was, surprisingly, well-preserved.

The Tarek Waly Center was able to repair the severe damage to the mud brick, and then re-plastered the building, fixed the plumbing issues, and added new doors and windows. Though the foundation had not been damaged, preventative measures were taken to ensure its security. Building materials used during conservation were sourced locally, or were recycled from the preexisting materials of the house. New floor tiles and decorative mosaic decoration on the walls were installed. Previous undocumented conservation efforts were reversed and fixed.

The Tarek Waly Center composed a thorough conservation report with photographs which is open access and available to download here.

Bibliography

Fathy, Hassan. Gourna: a Tale of Two Villages. Cairo: Ministry of Culture, 1969.

Maessen, Marcel. Living in Egypt: a House, a Home. In: Németh, Bori (ed.). Now Behold My Spacious Kingdom: Studies Presented to Zoltán Imre Fábián on the Occasion of His 63rd Birthday. Torino: L’Harmattan, 2017: 162-168.

Serageldin, Ismail. Hassan Fathy. Alexandria: The Bibliotheca Alexandria, 2007: 98-99.

Steele, James. An Architecture for People: The Complete Works of Hassan Fathy. Eastbourne: Gardners Books, 1997: 91-95.

Steele, James. The Hassan Fathy Collection. A Catalogue of Visual Documents at the Aga Khan Award for Architecture. Bern: The Aga Khan Trust for Culture, 1989: 19.

Warner, Nicholas. Clarke/Fathy: Reviving Traditions. In: El-Wakil, Leila (ed.). Hassan Fathy: An Architectural Life. Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press, 2018: 268-269.