Theodore Davis House

About

About

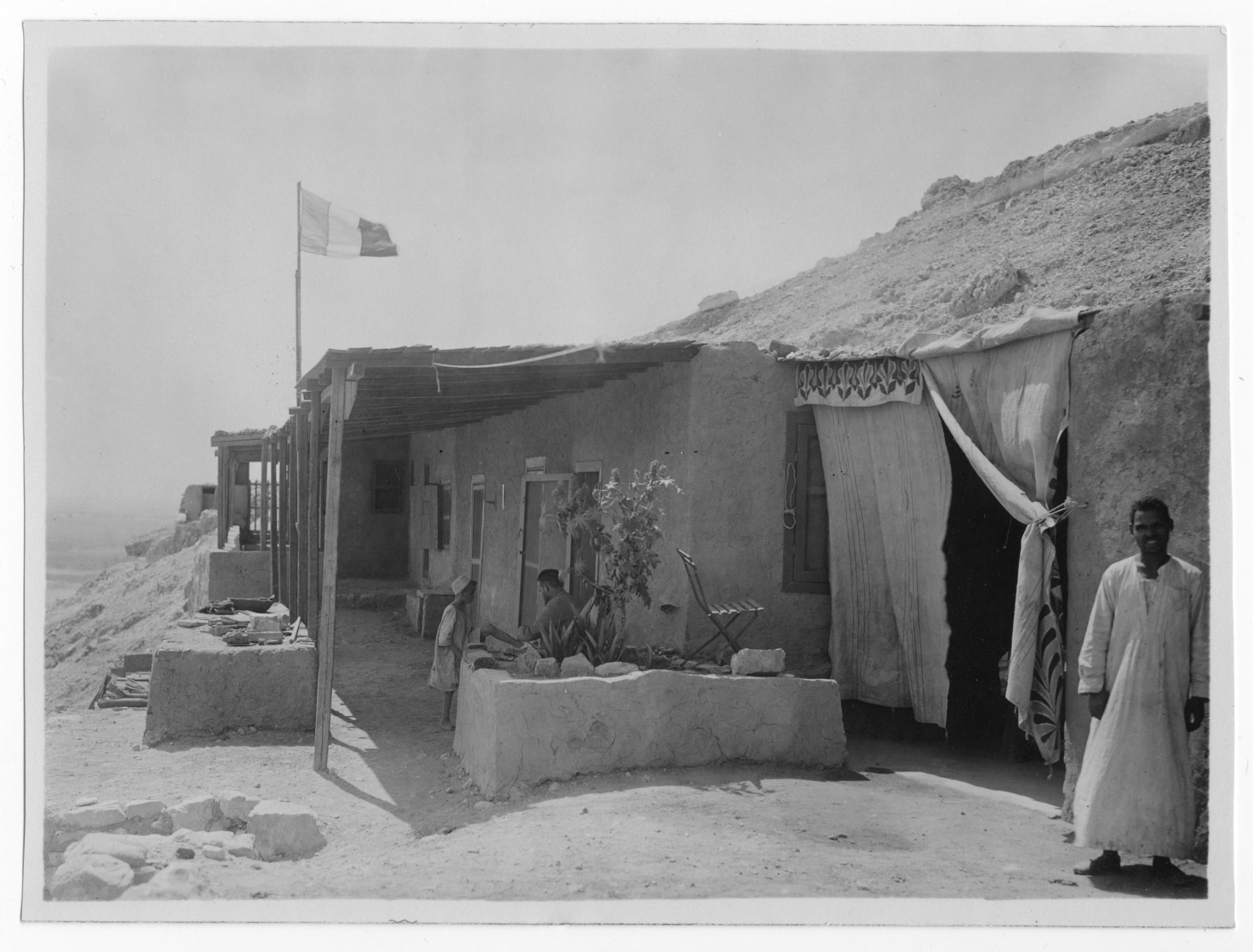

During the 1905-1906 season, Edward Ayrton, then employed by Theodore Davis, oversaw the construction of a new dig house set within the base of the cliffs of the Western Valley, and has henceforth been called Davis House. The house appears to have been made of irregularly shaped stone embedded in mud and covered over with a mud plaster. It benefitted from the afternoon shade provided by nearby low cliffs, and a double wooden roof, similar to other historic dig houses, that helped keep the house cool.

The original plan of the house consisted of a study, dining room, and four bedrooms, but some time before World War I, it was expanded to include a kitchen, guards’ hut, antiquities storeroom, an artist’s studio, and a darkroom for photography. Originally, it did not have access to water or electricity. The house had a flat roof, but at some point, possibly in the 21st century, an expansion to the house included the construction of a sizable dome.

Site History

The American businessman, Theodore Davis (1837-1915), came from a poor family. Self-educated, he was nevertheless able to become a successful lawyer and a very wealthy man through dealings during the American Civil War. Fascinated by stories his friends told about the treasures of ancient Egypt, Davis first traveled there in 1887 and became convinced that there were many more treasure that only awaited his enthusiasm and good luck to uncover. In 1897, he built an opulent dahabiyeh, the Beduin, in which he began regular trips on the Nile, visiting the many sites on its shore. But the more he listened to various European archeologists talk of their exploits, the more he became convinced that Thebes was where treasure was most likely to be found.

So, in 1901 he hired a young man, Howard Carter, to excavate on his behalf in the Valley of the Kings (KV). Within two years, his team had found several tombs, including the richly furnished tomb of Thutmes IV (KV 43, in 1903) and the enigmatic tomb of Hatshepsut (KV 20, in 1904).

Shortly thereafter, when Carter was transferred by the Antiquities Service to Saqqara, Davis continued work in the Valley with only his team of local workmen. His luck continued, and in 1905 he uncovered KV 46, the unplundered tomb of Yuya and Thuyu, the parents of Amenhetep III. It was then the richest tomb ever found in KV and would remain so until the discovery of KV 62, the tomb of Tutankhamen, 17 years later.

Continuing to search the Valley, Davis’s goal was always to find treasure-filled tombs. Ironically, he hired a young Englishman, Edward Ayrton, a serious archaeologist who held such treasure-hunting in low regard. But, perhaps following Davis’s “nose for treasure,” Ayrton found KV 56, called “the Gold Tomb,” filled with 78 amulets, pendants, bracelets, and necklaces, all of gold, silver, and electrum. “It would seem that I have more success than any other explorer,” Davis wrote, taking credit for its discovery, but his lack of concern for any of the objects not of gold and silver was commented on by several visiting Egyptologists. One described seeing Davis tear apart some recently discovered ancient floral collars made of papyrus and Faience beads to show lunch guests “how strong they were.” Davis’s reputation as a benefactor of archaeology suffered greatly from this and other similar stories.

Early in his employment, Ayrton suggested that their work would benefit if its headquarters were in the field, close to the work, with cleaning and photographic facilities and living quarters. Davis agreed, and “Davis House” was built at the entrance to the West Valley of the Kings. The site was carefully chosen, doubtless at Ayrton’s suggestion, located so as not to interfere with the view of the Valley tourist first saw as they walked from their donkeys and horses.

No one was associated with more discoveries in the Valley of the Kings than Davis—perhaps 30 tombs were found by his crews—and, for a time, he was the most famous excavator in the world. Tea at Davis House with him and his staff became a sought-after occasion. Davis himself found the House appealing, and he regularly used it to entertain the many VIPs who came to KV. Among them were J.P. Morgan and Theodore Roosevelt. The Duke and Duchess of Cornwall insisted on lunch with Davis at the house as an absolutely must on their Luxor visit.

With scores of discoveries and worldwide fame, Davis’s life seems charmed. Finally, however, in 1914, age and ill health forced him to abandon his searches for treasure. He described the Valley of the Kings as being “exhausted,” and he returned America, where he died in 1915, seven years before Howard Carter discovered the tomb of Tutankhamen.

Essay by Dr. Kent Weeks

Dating

This site was used during the following period(s):

Exploration

Conservation

Conservation History

Like all buildings of mud, mudbrick, and stone, Davis House required regular maintenance to survive. After Davis’s death, when it sat idle, it quickly fell into ruin. Sixty years later, however, in 1978, John Romer, who was then exploring the Valley, undertook its restoration and enlargement, and made it his field headquarters. When his work ended, the house briefly served as a residence for local inspectors of antiquity. For the past three decades, however, Davis House has sat empty. Perhaps one day it can become a small museum, illustrating one of the most important periods in the history of KV archaeology.

Bibliography

Davis, Theodore M., Gaston Maspero, Georges Daressy and L. Crane. The Tombs of Harmhabi and Touatânkhamonou (= Theodore M. Davis' Excavations, Biban el Moluk, 6). London, 1912.

Romer, John. Valley of the Kings. 1st ed. New York: Morrow, 1981: pp. 204-205, 236-237.